November 30, 2022

There are no birds. Richard Shelton, the man who reached out to me in a very dark place, is gone. After many days at his bedside, now I find comfort in his poetry. Because, in the end, all you become are words.

The wife’s favorite Dick Shelton poem is “The Hole,” which he read at the graduation ceremony for her master’s degree so many years ago. It is about an excavation in his yard, a hole that “moves with great care and precision between the stars.” In his book of what he calls “incomplete fictions,” The Other Side of the Story, “The Hole” immediately precedes my favorite, “The Stones.”

I think about this poem every time I drive up his driveway with its long wall of stones set in place without mortar (usually falling down in places). He wrote “The Stones” as he worked to lay up this wall. Just as he wrote “The Hole” while digging up the ground for the cement pool—his “trap for goldfish”—that now waters his gray herd of javelina.

“I love to go out on summer nights and watch the stones grow,” he begins, insisting that younger stones move about more than what their elders consider is good for them, that old stones prefer to remain comfortably where there are, getting fat as a matter of distinction.

Whenever I read “The Stones,” I imagine him standing in the desert of his yard, talking to the young stones of his wall as he piles them on top of the old, fat ones, working through the heat of the evening as the sun retreats and the moon rises large and silver above the distant Rincon Mountains.

The moon, he writes at the end of the piece, is always spoken of in whispers by the elder stones. “Feel how it pulls at us,” one says, “urging us to follow.” Another says, “It is a stone gone mad.”

Dick placed thousands of stones carefully atop one another, forming a high wall that contours the long curve of the dirt drive to his house. How many late-night hours did that take? He always refuses my offer to help with repairs, insisting that he alone can properly set stone upon stone.

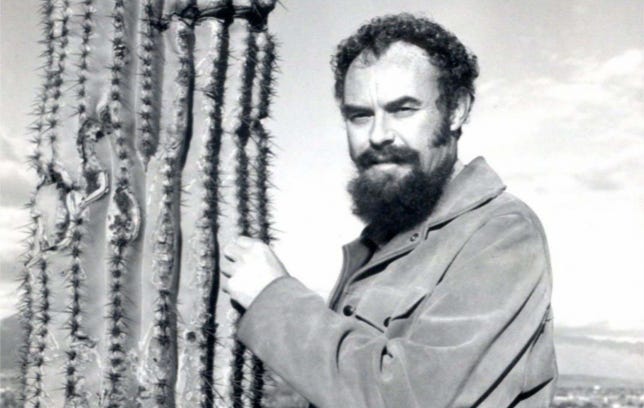

I can see him now, walking the undisciplined squad of his wall in the moonlight, his arms raised like the semaphore saguaros surrounding him. He admonishes the young stones to remain with their elders, unconcerned about his neighbors closing their blinds to the lunatic poet.

Richard Shelton, mentor, friend, godfather to my children, teacher of stones.

Like me (and so many others), my youngest daughter was also his student. Today, after returning to Flagstaff from Dick’s home, she dug out this poem to share with me.

Talking to Stones

--for Dick Shelton

Bits of the wall always fell down.

You never used mortar.

I imagined you out in the evenings

making amends,

refitting the pieces together,

talking to them, smoothing them with your hands,

saying, Stay put

knowing they wouldn’t.

We’d take the dogs out on walks

in the arroyos,

filling our pockets with pennies,

wayward tennis balls, bits of tumbled glass.

us girls on rollerblades,

the dogs muscling forward,

too big

for any one of us to handle.

This many years later

I think you must have spent your evenings

hunched over the computer,

cursing the insolent keys.

So many words

to work into place without mortar.

This tearing down and building up.

Or maybe you simply curled up with the dogs

on the kitchen floor,

the even keel of their breathing

filling the house,

the lolling tongues, the happy eyes.

You would like that best,

to be remembered as worthy

of their company,

akin to their great hearts.

Beautiful. Thank you. Made me cry. This morning imagining the countless ways that Dick touched hearts and souls in his long lifetime, his many students. I am so grateful to be among those who knew Dick as teacher, friend, supporter. Thank you Ken for being at his side. I am sorry for your loss. So much love from here to the higher place where Dick's spirit now resides.

"arms raised like the semaphore saguaros surrounding him. He admonishes the young stones to remain" thank you for this gorgeous writing and most thoughtful sentiments about your friend. What a moving piece of writing, and inspirational for us.