Day 444 of the Pandemic (June 5, 2021)

No birds today. Walker Thomas is dead. My best friend and hiking compadre of 20 years died this morning after a bout with pancreatic cancer. Short and intense. But it wasn’t much of a fight. Cancer in a time of Covid. The VA Hospice called with the news.

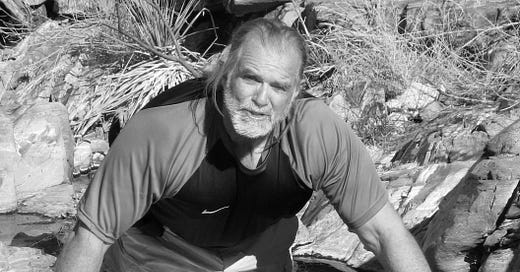

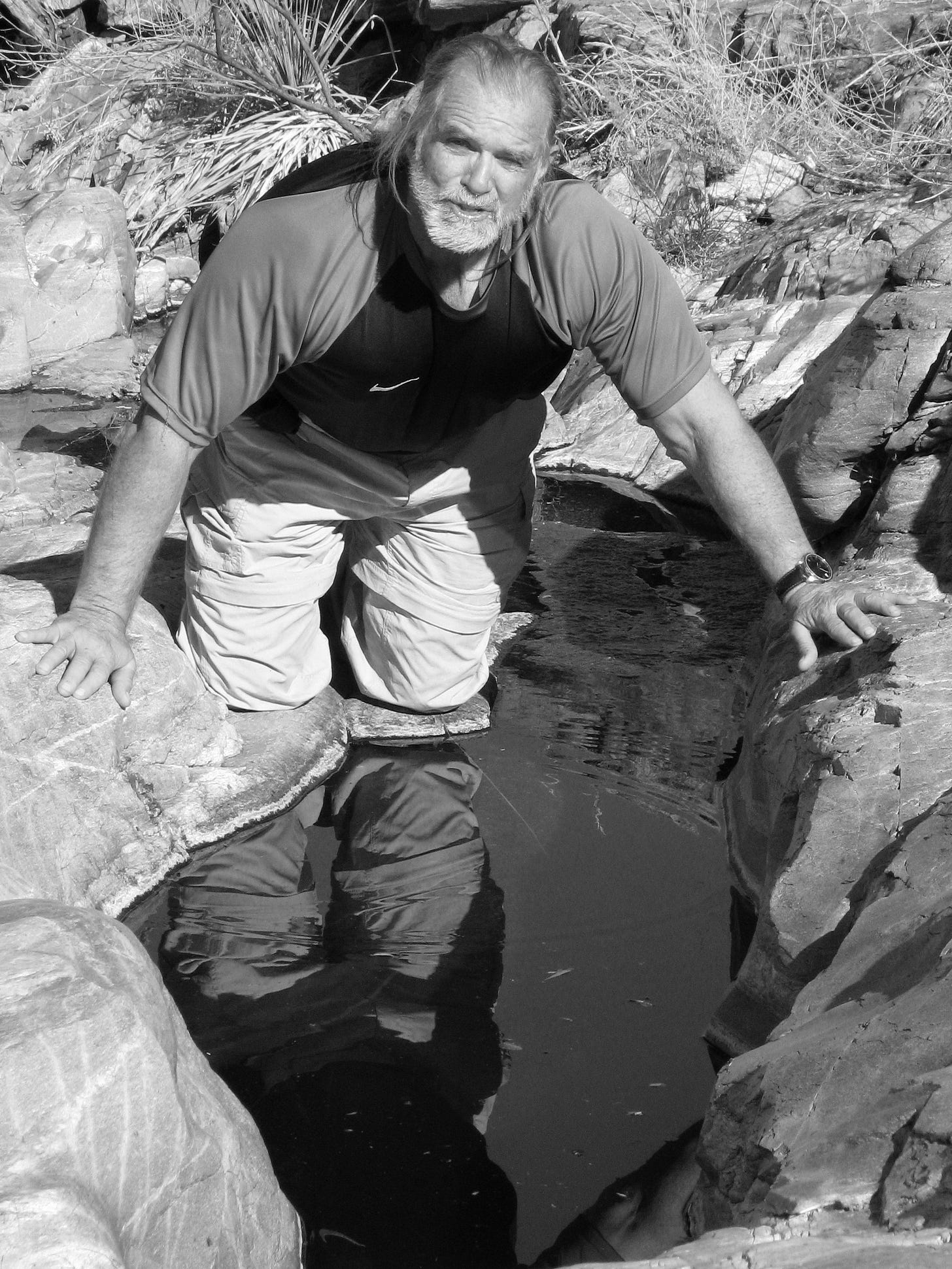

I saw him last night for a couple hours though he was unresponsive. I told him it was okay to go, that I had this, his book manuscript and apartment clear-out and final arrangements. That I would scatter his ashes at our favorite fishing hole in the White Mountains and leave some at his cave in the Rincon Mountains, if I could find it without him. I promised him I would see him on the other side. “I know you don’t believe all that,” I said. “But I have enough faith for both of us.”

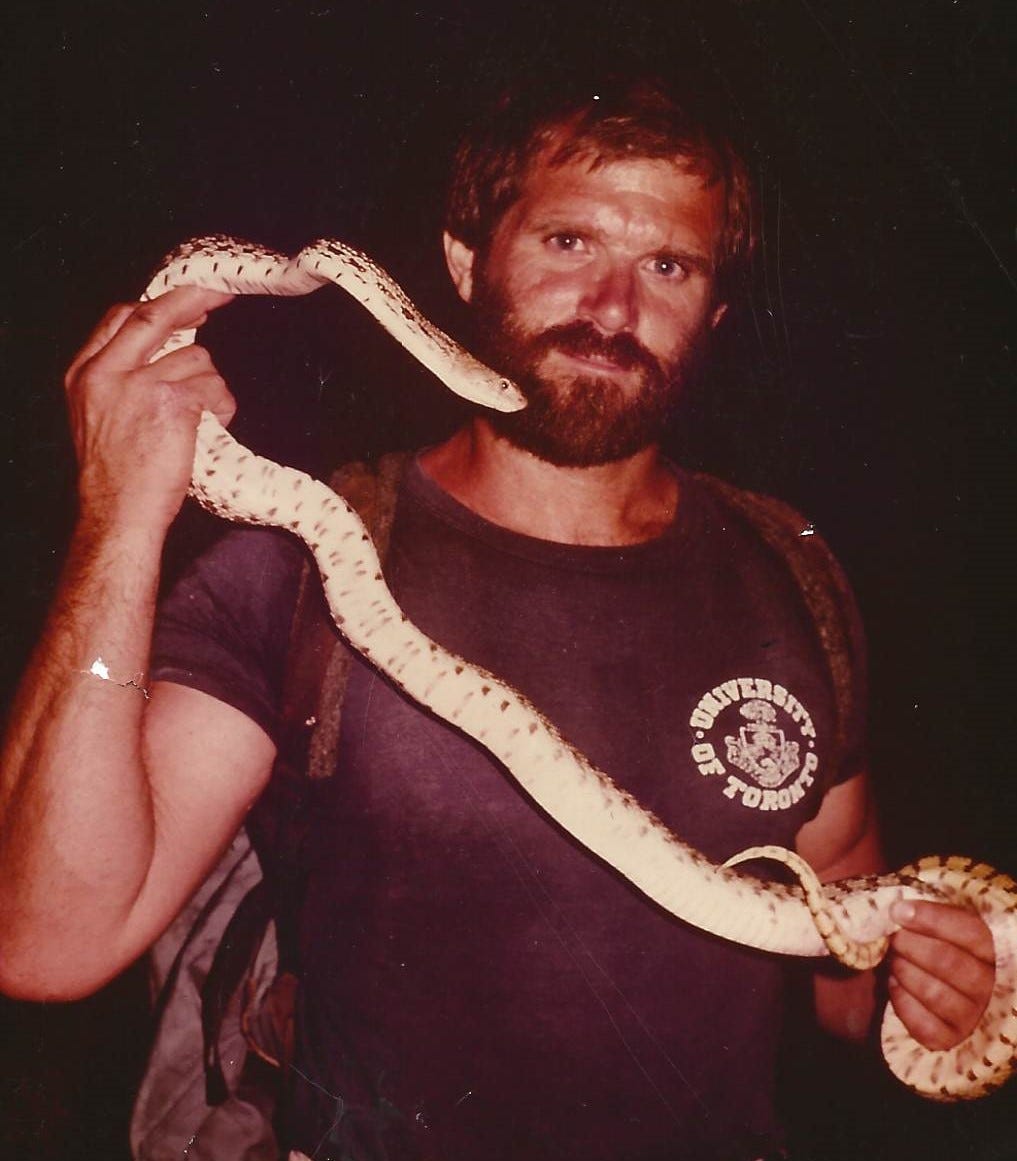

Walker entered my life twenty years ago after my youngest daughter came home from school one day and said: “We had a really weird substitute today, Dad. He lived in a cave.” I peppered her with questions, and she told me about his photographs of the animals he befriended during the eight years he spent on the mountain, about his story. “He knows you,” she said. “He’s writing a book.”

After reading his manuscript, Notes from a Solitary Beast, and being impressed with his writing style and ability, I asked him to join my creative writing workshop at the Poetry Center in Tucson. He had been friends with the writers Chuck Bowden and Ed Abbey. He showed me a story he published in Outside magazine in 1988. In it, he imagines himself in flight with a Townsend’s big-eared bat he shares the cave with, about the bears and skunks, foxes and ringtails that have become his companions. “I have come to feel less an intruder,” he says, “more a functional part of the environment. Life goes on around me, gaining from me where it can. Wherever we are, we become part of the nature that is there, despite ourselves.”

We made two attempts to reach his cave. Both failed. Neither one of us is young. In his late sixties, Walker no longer owned the steel-fibered muscles and bottomless stamina he had in the 1980s when he could out-hike a horse and rider, uphill. Even then, with eighty pounds on his back, it took him most of the night and part of the next day to reach his home—the cave where he lived the last few years of his decade on the mountain.

But we did spend many days hunting snakes in Arizona’s magnificent Sky Islands and fishing for brown trout at the East Fork of the Black River. More about this later.

The kind woman at the VA Hospice says she can’t release Walker’s ashes without a Will specifying cremation.

“But he has no Will,” I tell her, mentioning his last wishes were only spoken. “What happens to his body?”

“Oh, we take good care of him,” she assures me, “as unclaimed remains.”

There will be a time when we see our reflection, like in a dark mountain pool trapped in smooth stone, and we’ll know it’s the end because the face in the water is looking back at us.

Walker died as he lived. In obscurity. Almost an abstraction. His life was a wilderness ethic—leave no trace. His death is the same, but for the echoes in the landscape.

And now the birds were singing overhead, and there was a soft rustling in the undergrowth, and all the sounds of the forest that showed that life was still being lived blended with the souls of the dead in a woodland requiem. —Terry Pratchett

Sorry about your good friend. Two of my friends died suddenly this year so I know how you feel.

It's tough to watch a close friend dissolve before your eyes. He looks familiar, Ken. Do you know if he ever visited Julian Hayden out on his patio where he held court? I met both Bowden and Abbey there.