Day 324 of the Quarantine (February 1, 2021)

The snow has melted and the well is pumping again. Almost two and a half inches of precipitation for far this year. Maybe we’ll make it to April.

Forty species of birds for January. Mostly what I expect, but in the last few days the hermit thrushes have vanished, and more Cassin’s finches crack open sunflower seeds with scores of thistle-worrying pine siskins and house finches, the birds scrambling between feeders and the fountain.

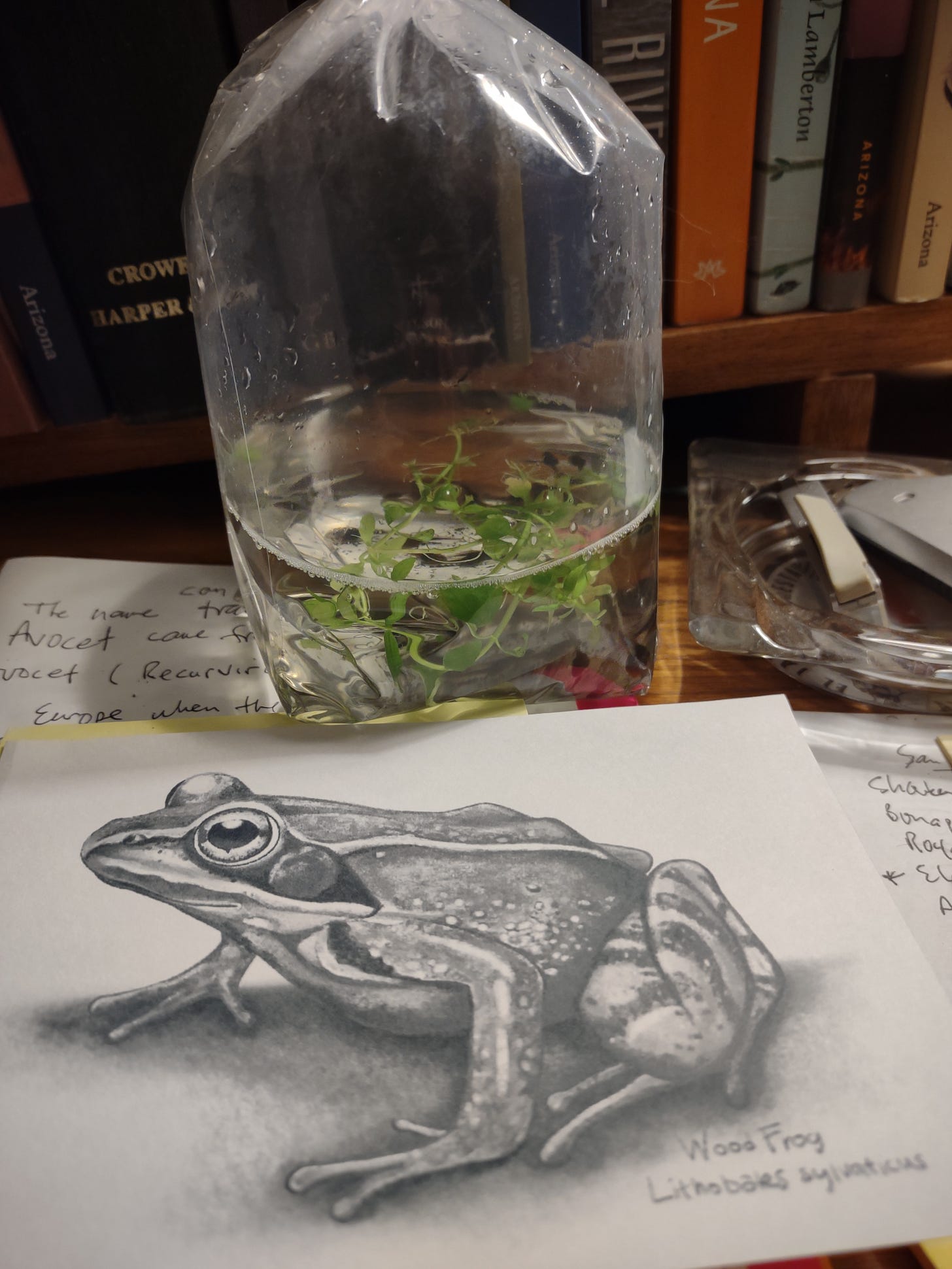

With the days getting longer, I’ve started planning for the Covid garden and fountain. I’ll plant the usual greens—kale, spinach, onions, cabbage, and lettuce—but the water feature needs more life. Native monkeyflower (Mimulus guttatus) for the trickling rocks and amphibians for the pond. We have canyon treefrogs and toads in the area, but I’m thinking about an amphibian that’s better adapted to the cold. Like the cold in Alaska and in my backyard. Like wood frogs. Thumb-sized, bug-eyed amphibians that can freeze solid and then thaw back to life. NASA is studying them for deep-space missions, the glucose in their blood allowing them to turn into ice cubes without damaging their cells, slowing their metabolism to near nothing. Then waking as the temperature rises. Tough as tardigrades.

They’ll be perfect, I think, every time I break the ice on the pond. But where to find them?

I do a quick Internet search and find a woman from northern Georgia who has wood frogs on her property and is selling tadpoles on eBay. I buy three dozen.

Along with my quantum bird theory, I’m leaning into another theory that wilderness is healthier when we properly manage it. The idea being that because humans and wilderness have evolved side-by-side, wilderness, which I’m defining here as the world apart from people (in truth, we are wilderness too), is dependent upon us.

A kind of multispecies or guild mutualism. Species benefiting each other by interacting with each other. Like humans and the internal wilderness of our gut flora, those hundreds of kinds of microbes in our intestines that outnumber all the cells in our body by a hundred-fold. We, as walking sacks of bugs, provide them a warm home and nourishment; they give us vitamins, protection from pathogens and toxins, and help digest our dinner, among other niceties.

Our relationship, good or bad, with the wilderness inside us is the same as with the wilderness surrounding us. That’s the idea, anyway.

I’m reading William Bryant Logan’s Sprout Lands: Tending the Endless Gift of Trees where he argues that some past and present methods of cultivating trees created the healthiest, most sustainable and most diverse woodlands the planet has ever known. Two of the many examples Logan explores are the Australian bush and California chaparral, how indigenous peoples used deliberate burning to improve the land for their food, materials, and medicine—to the point that without humans these places become degraded and less diverse.

Closer to home in Arizona, the tiny borderland oasis of Quitobaquito Springs has had a connection with people for thousands of years. Until recently, this was good for both.

Today, I begin an experiment in elevating the diversity of my tiny backyard oasis with wood frogs.

Thanks for subscribing! More to come!